The Biggest Piece of the Recession Puzzle

We’re entering a moment that feels a lot like 1999 or 2007. Recession calls are en vogue. Talk of an AI bubble is spreading, even from tech leaders. Market valuations have run far past what's typical relative to GDP. Tariffs may have a long term average of 10–20% which would shave 1-3% off GDP. Housing prices are still near 2021 highs, even though mortgage rates have doubled from 3% to 6%. The federal government is shut down, unemployment is creeping up, political risks are rising, and short-term rates are still higher than at any point in the 2010s.

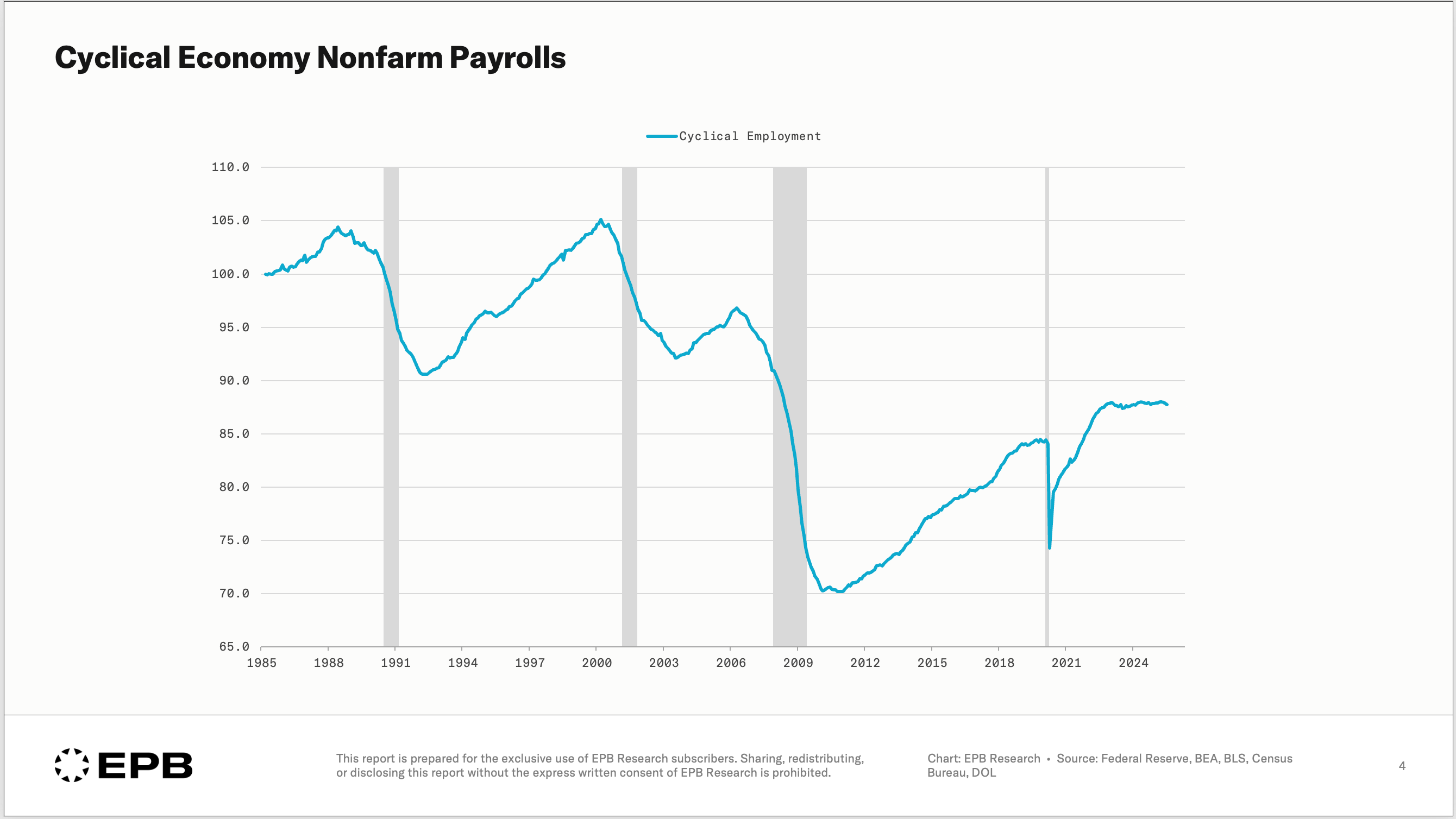

That’s quite a list. But there’s one key piece of the puzzle that almost never gets mentioned, and it’s the most useful in timing a recession: cyclical employment.

Why Total Employment Isn’t Enough

If you look at total employment on the St. Louis Fed’s FRED site, you’ll see that job levels usually peak right as a recession begins. Economists call that a coincident indicator. The National Bureau of Economic Research literally uses it as part of the definition of a recession. In other words, when employment turns, the recession is already here. If you watch total employment, you’ll always be behind the curve.

The Hidden Leaders: Residential Construction and Durable Goods

What leads employment is cyclical employment, jobs in industries that swing hardest with the business cycle. Two sectors matter most: residential construction and durable goods manufacturing (think autos, appliances, furniture). These are where layoffs start first and hardest when the economy turns down. They make up less than 20% of the U.S. economy, yet they often set off the broader unemployment cascade.

Eric Basmajian at EPBResearch is one of the few analysts who tracks this closely. His charts show that declines in these sectors have consistently led every modern recession, COVID aside. And right now, they’ve only just begun to edge down.

The Surprising Strength So Far

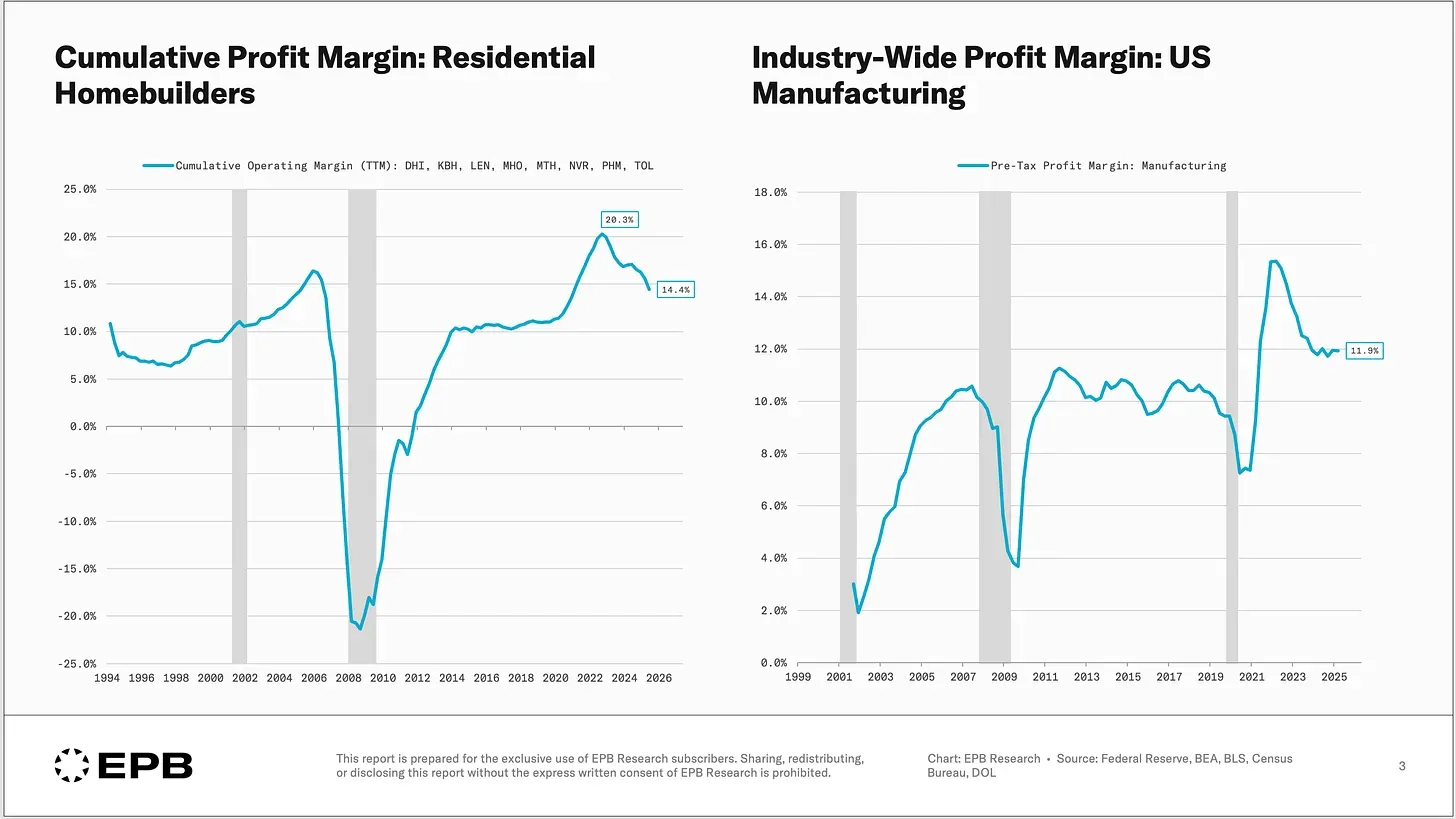

Given the size of the rate hikes since 2022, it’s remarkable that these sectors held up this long. Normally, they’d roll over much sooner. Profit margins explain part of that resilience.

Even after short-term rates surged, margins remain historically high. Many CEOs remember the chaos of firing and rehiring during COVID and have tried to hold onto staff longer than usual. But residential construction margins are now falling fast. With new tariffs on steel, a prolonged trade war with China, and persistently high rates, manufacturing may soon follow.

Why This Matters Now

Cyclical employment is one of the best early warning systems we have. It gives a clear picture of when recession risks are rising before it shows up in total employment or GDP. Yet right now, that data is harder to access. The Bureau of Labor Statistics, which normally provides these numbers, is closed during the government shutdown, and its leadership was recently removed under political pressure.

So what happens if the data gets delayed or distorted? How do we keep track of one of the most important indicators of the economy?

A Better Way to Watch the Canary

No, an LLM can’t help with this. But classical machine learning can. I’ve built and trained a regression model to estimate residential construction employment using other economic inputs. It performs surprisingly well and offers a way to track this critical variable even when the official data is offline.

My next post will walk through how the model works and what it says about where we are in the cycle today. Once the BLS reopens, we’ll be able to compare the model’s estimates against the real data and see if anything looks off.